It’s easy to talk about infrastructure maintenance needs, but much harder to figure out how those needs should be addressed, when they should be addressed, and who should be responsible for them. In this post, we’ll discuss some of the key influencers behind infrastructure decisions and how those decisions get financed and turned into reality.

As we’ve mentioned before, state DOTs are the organizations with the political and practical resources to effect transportation and infrastructure reform. Some state DOTs (e.g., California and New Jersey) have begun to reverse spending trends from prioritizing new construction to investing in maintenance and repairs, resulting in better road conditions state-wide. In other states, public engineers like Charles Marohn seek to promote public awareness of the infrastructure maintenance needs, leading the way forward for communities to grow and thrive without sacrificing future sustainability.

It’s still common, however, for states to allocate a high percentage of their transportation budget to building new roads. Why? Streetsblog USA offers the following three reasons for the seeming governmental preference for building new roads and bridges over servicing the existing ones:

- Building new infrastructure is less complicated than fixing existing infrastructure.

- New projects tend to be more popular with the public.

- New construction is easier to finance.

Reason #3 brings us to the matter of financing new projects. The Center on Budget and Policy Priority report on infrastructure calls state and local governments the “stewards” of most of the nation’s infrastructure, citing the fact that state and local governments “own over 90% of non-defense public infrastructure assets.” The report explains that, while federal grants and subsidies often contribute to upkeep public infrastructure, state and local governments cover roughly 75% of maintenance and improvement costs.

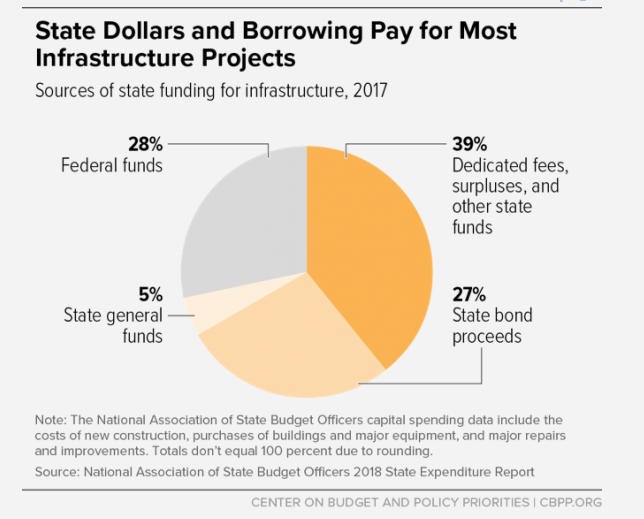

So how do the smaller levels of government fund these projects? As reflected in the graph below, they use a variety of methods and sources including borrowing (often in the form of bonds), taxes and fees, federal grants, and public-private partnerships.

Of course, these percentages vary from state to state. States that don’t borrow as much tend to draw more heavily from general state funds, etc., but for the most part, these are the funding sources that collectively comprise infrastructure budgets created by state DOTs throughout the nation.